Missing Semester Lecture 7 - Debugging and Profiling

MIT The Missing semester Lecture of Your CS Education Lecture 7 - Debugging and Profiling

Profiling

Even if your code functionally behaves as you would expect, that might not be good enough if it takes all your CPU or memory in the process. Algorithms classes often teach big O notation but not how to find hot spots in your programs. Since premature optimization is the root of all evil, you should learn about profilers and monitoring tools. They will help you understand which parts of your program are taking most of the time and/or resources so you can focus on optimizing those parts.

Timing

Similarly to the debugging case, in many scenarios it can be enough to just print the time it took your code between two points. Here is an example in Python using the time module.

1 | import time, random |

However, wall clock time can be misleading since your computer might be running other processes at the same time or waiting for events to happen. It is common for tools to make a distinction between Real, User and Sys time. In general, User + Sys tells you how much time your process actually spent in the CPU (more detailed explanation here).

- Real - Wall clock elapsed time from start to finish of the program, including the time taken by other processes and time taken while blocked (e.g. waiting for I/O or network)

- User - Amount of time spent in the CPU running user code

- Sys - Amount of time spent in the CPU running kernel code

For example, try running a command that performs an HTTP request and prefixing it with time. Under a slow connection you might get an output like the one below. Here it took over 2 seconds for the request to complete but the process only took 15ms of CPU user time and 12ms of kernel CPU time.

1 | $ time curl https://missing.csail.mit.edu &> /dev/null |

Profilers

CPU

Most of the time when people refer to profilers they actually mean CPU profilers, which are the most common. There are two main types of CPU profilers: tracing and sampling profilers. Tracing profilers keep a record of every function call your program makes whereas sampling profilers probe your program periodically (commonly every millisecond) and record the program’s stack. They use these records to present aggregate statistics of what your program spent the most time doing. Here is a good intro article if you want more detail on this topic.

Most programming languages have some sort of command line profiler that you can use to analyze your code. They often integrate with full fledged IDEs but for this lecture we are going to focus on the command line tools themselves.

In Python we can use the cProfile module to profile time per function call. Here is a simple example that implements a rudimentary grep in Python:

1 | #!/usr/bin/env python |

We can profile this code using the following command. Analyzing the output we can see that IO is taking most of the time and that compiling the regex takes a fair amount of time as well. Since the regex only needs to be compiled once, we can factor it out of the for.

1 | $ python -m cProfile -s tottime grep.py 1000 '^(import|\s*def)[^,]*$' *.py |

A caveat of Python’s cProfile profiler (and many profilers for that matter) is that they display time per function call. That can become unintuitive really fast, especially if you are using third party libraries in your code since internal function calls are also accounted for. A more intuitive way of displaying profiling information is to include the time taken per line of code, which is what line profilers do.

For instance, the following piece of Python code performs a request to the class website and parses the response to get all URLs in the page:

1 | #!/usr/bin/env python |

If we used Python’s cProfile profiler we’d get over 2500 lines of output, and even with sorting it’d be hard to understand where the time is being spent. A quick run with line_profiler shows the time taken per line:

1 | $ kernprof -l -v a.py |

Memory

In languages like C or C++ memory leaks can cause your program to never release memory that it doesn’t need anymore. To help in the process of memory debugging you can use tools like Valgrind that will help you identify memory leaks.

In garbage collected languages like Python it is still useful to use a memory profiler because as long as you have pointers to objects in memory they won’t be garbage collected. Here’s an example program and its associated output when running it with memory-profiler (note the decorator like in line-profiler).

1 | @profile |

1 | $ python -m memory_profiler example.py |

Event Profiling

As it was the case for strace for debugging, you might want to ignore the specifics of the code that you are running and treat it like a black box when profiling. The perf command abstracts CPU differences away and does not report time or memory, but instead it reports system events related to your programs. For example, perf can easily report poor cache locality, high amounts of page faults or livelocks. Here is an overview of the command:

perf list- List the events that can be traced with perfperf stat COMMAND ARG1 ARG2- Gets counts of different events related to a process or commandperf record COMMAND ARG1 ARG2- Records the run of a command and saves the statistical data into a file calledperf.dataperf report- Formats and prints the data collected inperf.data

Resource Monitoring

Sometimes, the first step towards analyzing the performance of your program is to understand what its actual resource consumption is. Programs often run slowly when they are resource constrained, e.g. without enough memory or on a slow network connection. There are a myriad of command line tools for probing and displaying different system resources like CPU usage, memory usage, network, disk usage and so on.

- General Monitoring - Probably the most popular is

htop, which is an improved version oftop.htoppresents various statistics for the currently running processes on the system.htophas a myriad of options and keybinds, some useful ones are:<F6>to sort processes,tto show tree hierarchy andhto toggle threads. See alsoglancesfor similar implementation with a great UI. For getting aggregate measures across all processes,dstatis another nifty tool that computes real-time resource metrics for lots of different subsystems like I/O, networking, CPU utilization, context switches, &c. - I/O operations -

iotopdisplays live I/O usage information and is handy to check if a process is doing heavy I/O disk operations - Disk Usage -

dfdisplays metrics per partitions anddudisplays disk usage per file for the current directory. In these tools the-hflag tells the program to print with human readable format. A more interactive version ofduisncduwhich lets you navigate folders and delete files and folders as you navigate. - Memory Usage -

freedisplays the total amount of free and used memory in the system. Memory is also displayed in tools likehtop. - Open Files -

lsoflists file information about files opened by processes. It can be quite useful for checking which process has opened a specific file. - Network Connections and Config -

sslets you monitor incoming and outgoing network packets statistics as well as interface statistics. A common use case ofssis figuring out what process is using a given port in a machine. For displaying routing, network devices and interfaces you can useip. Note thatnetstatandifconfighave been deprecated in favor of the former tools respectively. - Network Usage -

nethogsandiftopare good interactive CLI tools for monitoring network usage.

Exercises

Debugging

- Use

journalctlon Linux orlog showon macOS to get the super user accesses and commands in the last day. If there aren’t any you can execute some harmless commands such assudo lsand check again.

1 | $ journalctl --since="1d ago" | grep sudo |

Profiling

- Here are some sorting algorithm implementations. Use

cProfileandline_profilerto compare the runtime of insertion sort and quicksort. What is the bottleneck of each algorithm? Use thenmemory_profilerto check the memory consumption, why is insertion sort better? Check now the inplace version of quicksort. Challenge: Useperfto look at the cycle counts and cache hits and misses of each algorithm.

1 | $ python -m cProfile -s tottime sorts.py 1000 |

Using cProfile, it looks like the speed is sorted by: quicksort < quicksort_inplace < insertionsort.

1 | $ kernprof -l -v sorts.py |

Using line_profile, we can find that the while loop is the bottleneck of insertion sort, while the double for loops is the bottleneck of quick sort.

Using

memory_profilerfor insertion sort:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16$ python3 -m memory_profiler sorts.py

Filename: sorts.py

Line # Mem usage Increment Occurrences Line Contents

=============================================================

11 15.730 MiB 15.730 MiB 1000 @profile

12 def insertionsort(array):

13

14 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 26096 for i in range(len(array)):

15 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 25096 j = i-1

16 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 25096 v = array[i]

17 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 230871 while j >= 0 and v < array[j]:

18 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 205775 array[j+1] = array[j]

19 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 205775 j -= 1

20 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 25096 array[j+1] = v

21 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 1000 return arrayUsing

memory_profilerfor quick sort:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13$ python3 -m memory_profiler sorts.py

Filename: sorts.py

Line # Mem usage Increment Occurrences Line Contents

=============================================================

24 15.730 MiB 15.730 MiB 33910 @profile

25 def quicksort(array):

26 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 33910 if len(array) <= 1:

27 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 17455 return array

28 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 16455 pivot = array[0]

29 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 157526 left = [i for i in array[1:] if i < pivot]

30 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 157526 right = [i for i in array[1:] if i >= pivot]

31 15.730 MiB 0.000 MiB 16455 return quicksort(left) + [pivot] + quicksort(right)

The reason why insertion sort is better than quick sort is that in the last step of quick sort, it concatenates which requires extra memory unlike insertion sort which changes its values in place.(Although we can’t get this conclusion through my probe result ^^)

- Using

perfto probe:

1 | $ perf record -e cache-misses python3 sorts.py |

Here’s some (arguably convoluted) Python code for computing Fibonacci numbers using a function for each number.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15#!/usr/bin/env python

def fib0(): return 0

def fib1(): return 1

s = """def fib{}(): return fib{}() + fib{}()"""

if __name__ == '__main__':

for n in range(2, 10):

exec(s.format(n, n-1, n-2))

# from functools import lru_cache

# for n in range(10):

# exec("fib{} = lru_cache(1)(fib{})".format(n, n))

print(eval("fib9()"))Put the code into a file and make it executable. Install prerequisites:

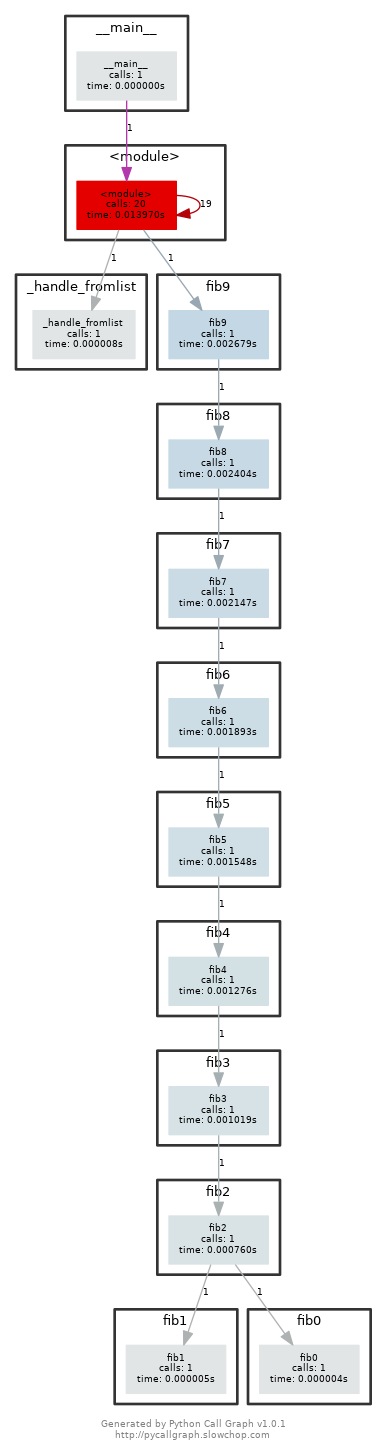

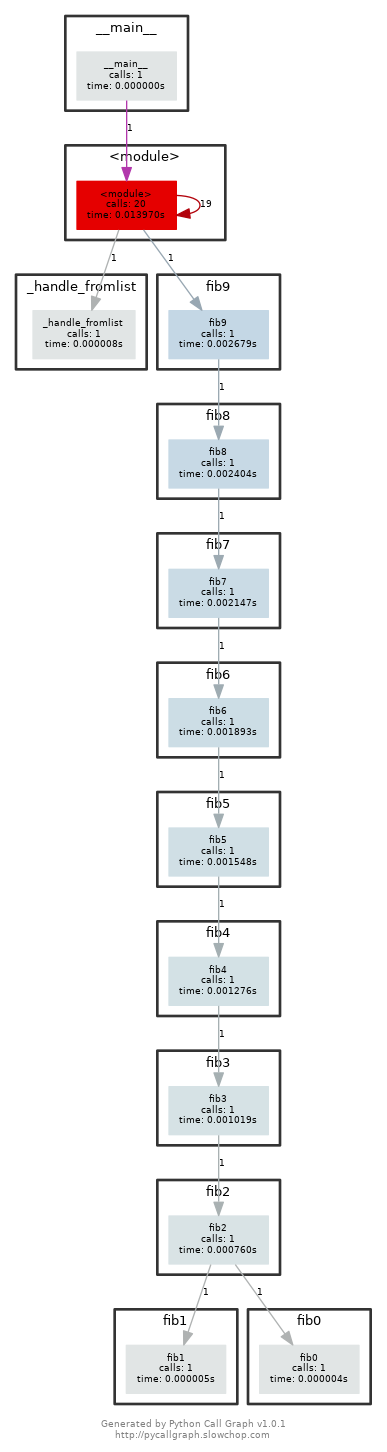

pycallgraphandgraphviz. (If you can rundot, you already have GraphViz.) Run the code as is withpycallgraph graphviz -- ./fib.pyand check thepycallgraph.pngfile. How many times isfib0called?. We can do better than that by memoizing the functions. Uncomment the commented lines and regenerate the images. How many times are we calling eachfibNfunction now?After execute

pycall graph graphviz -- ./fib.py, the generatedpycallgraph.pngfile is:

We can find that thefib0is called 21 times.After we uncomment the commented lines and regenerate the images, we can find the graph looks like this:

A common issue is that a port you want to listen on is already taken by another process. Let’s learn how to discover that process pid. First execute

python -m http.server 4444to start a minimal web server listening on port4444. On a separate terminal runlsof | grep LISTENto print all listening processes and ports. Find that process pid and terminate it by runningkill <PID>.

execute

python -m http.server 4444to start a web server:1

2$ python3 -m http.server 4444

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 4444 (http://0.0.0.0:4444/) ...run

lsof | grep LISTEN:1

2$ lsof | grep LISTEN

python3 8525 root 3u IPv4 31943 0t0 TCP *:krb524 (LISTEN)kill server:

1

2

3

4

5$ kill 8525

$ python3 -m http.server 4444

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 4444 (http://0.0.0.0:4444/) ...

已终止

- Limiting a process’s resources can be another handy tool in your toolbox. Try running

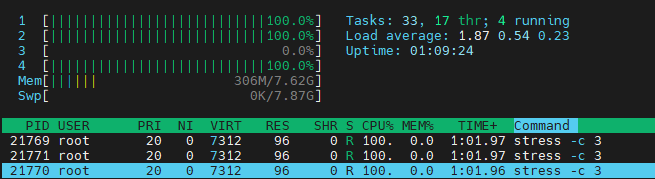

stress -c 3and visualize the CPU consumption withhtop. Now, executetaskset --cpu-list 0,2 stress -c 3and visualize it. Isstresstaking three CPUs? Why not? Readman taskset.

Run

stress -c 3:1

2$ stress -c 3

stress: info: [21768] dispatching hogs: 3 cpu, 0 io, 0 vm, 0 hddThen run

htopwe can find:

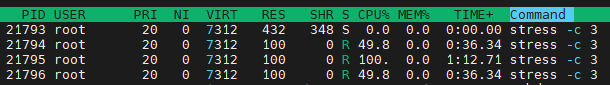

Execute

taskset --cpu-list 0,2 stress -c 3and runhtop:

We can findstressjust take one cpu. Because inman tasksetsaid: The Linux scheduler will honor the given CPU affinity and the process will not run on any other CPUs.